TIER

“On the walls of the cave, only the shadows are the truth.”

(Plato, The Allegory of the Cave, Republic, Book VII)

In the famous “Allegory of the Cave” Plato explores the tension generated by the multiple representations of reality.

In the context of this exhibition, this myth could be a clue to disclosing the topics behind Maximilian Prüfer’s new body of works. What is the knowledge of that single individual who finally went out of the cave and saw the forms of the real world? What is the knowledge of his companions? And ultimately, what is the knowledge originated by the sum of the visual knowledges of all the men, and where does it lie?

Taken as a whole, Maximilian Prüfer’s research is a multidisciplinary study including philosophy, semiotics and biology, aiming to investigate the multifold approaches to the world understanding through the utilization of insects and environmental phenomena. His work tends to highlight what could superficially be perceived of as natural random activity, detached from human-scale concerns. Gathering together knowledge from different realms, the artist’s practice stages ontological issues within the context of neurological and behavioral biologic mechanisms.

The new body of works engages and expands on topics disclosed by the artist in previous works, pursuing a formal research on the creation of objects by using living insects. The effort to give a tangible form to ephemeral and invisible – to the humans – natural elements drives the investigation, although becoming a secondary interest. The artist now exhibits a new code, staged with a documentation that has become his artistic sign, where micro events recall macro phenomena – the forming of raindrops recalling the creation of stars, for instance.

The analogy between insects and humans, and the displacement of authorship, are rather integral bases for the disclosing of the author’s new discourse.

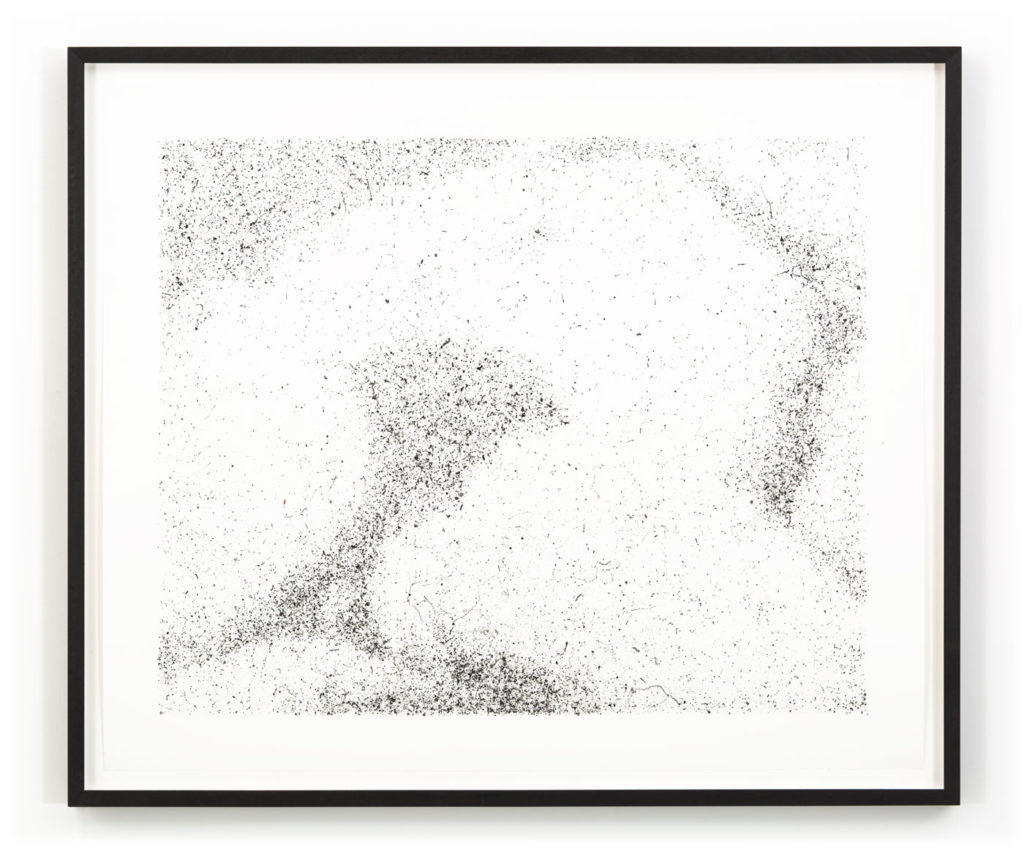

In his series “Naturantypie” Prüfer has involved the creativity of nature in many different ways. His gesture is suspended between observation and control: imprinting raindrops (Rain Pictures, 2015- ), tracking snails’ footprints (Snail Pictures, 2015- ), transferring scales of butterfly wings onto paper (Butterflies Prints, 2015). While giving instructions to nature, he also captures its elusiveness. Like in previous works – for instance Society, 2015 where he captured traces of ants – controlling and at the same time allowing a degree of freedom remains the crucial scientific procedure for the outcome of the new works, and their significance.

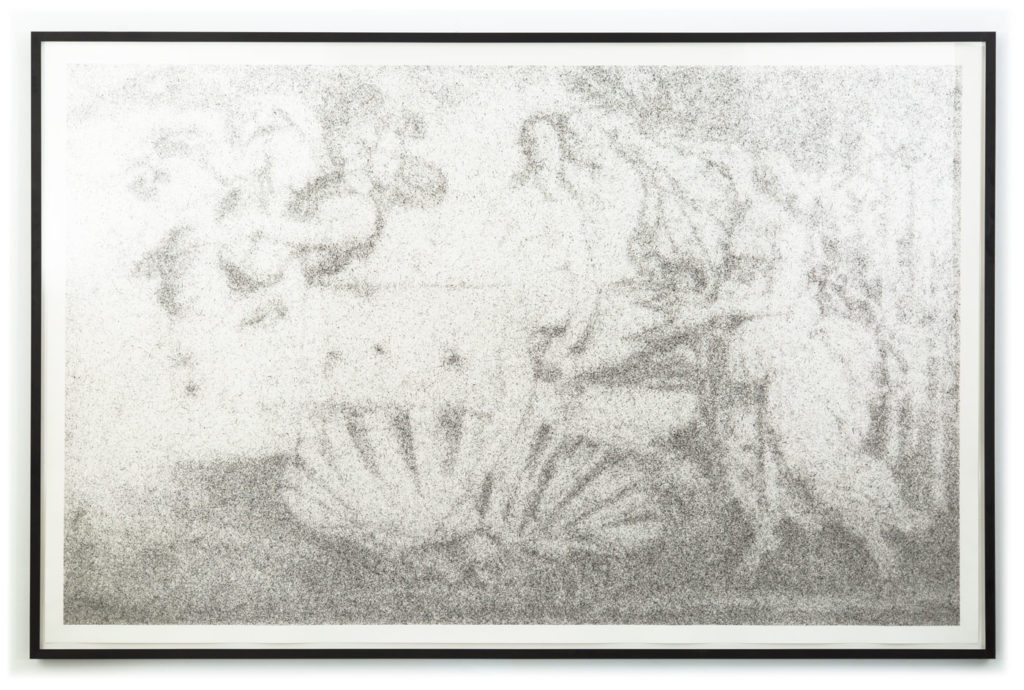

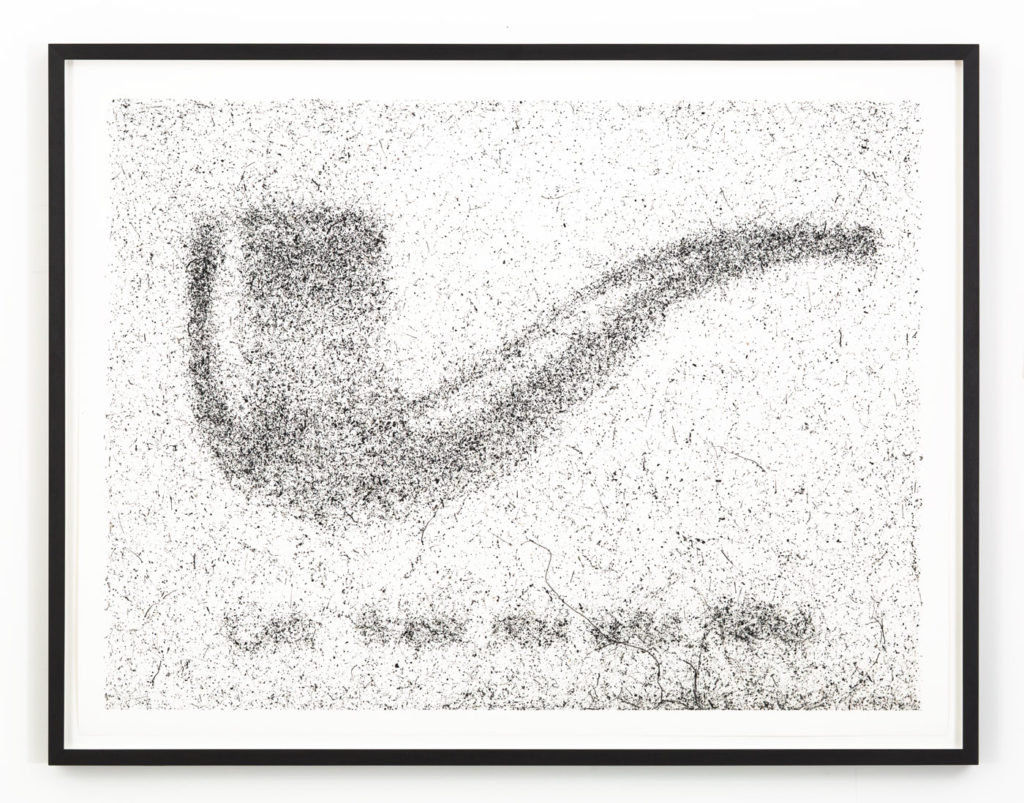

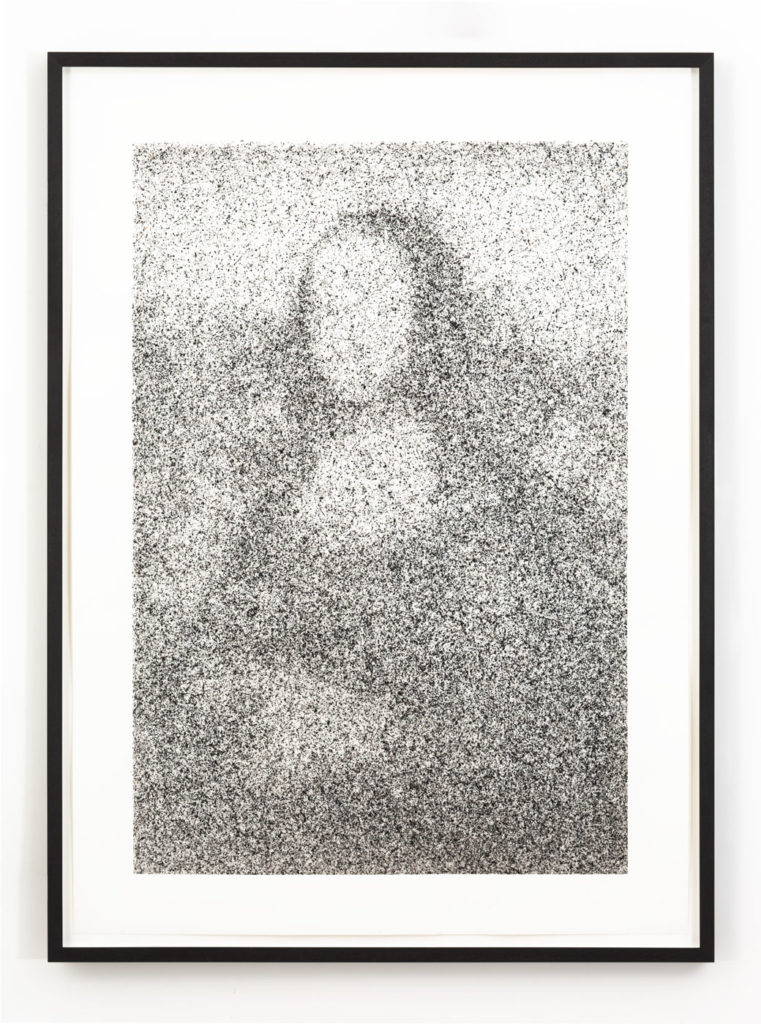

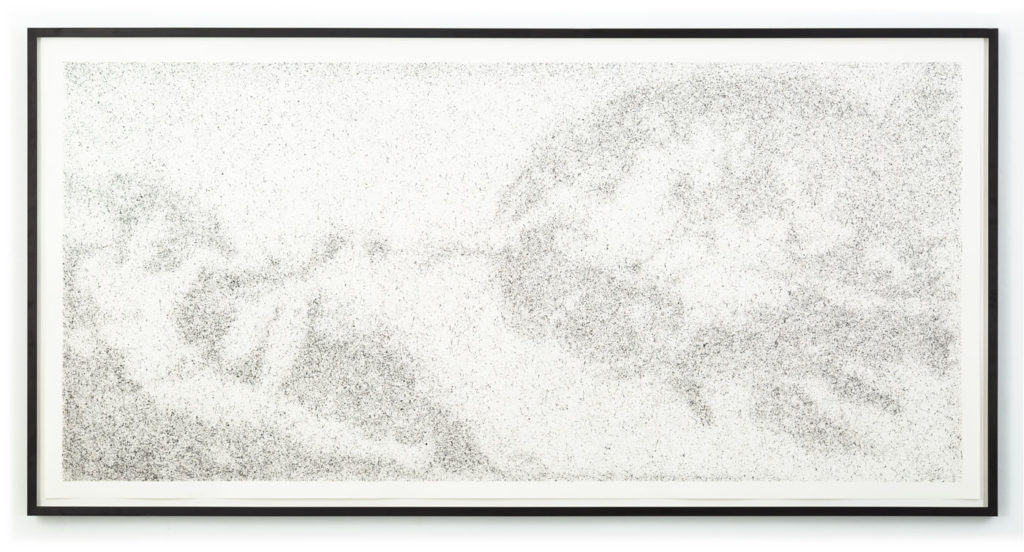

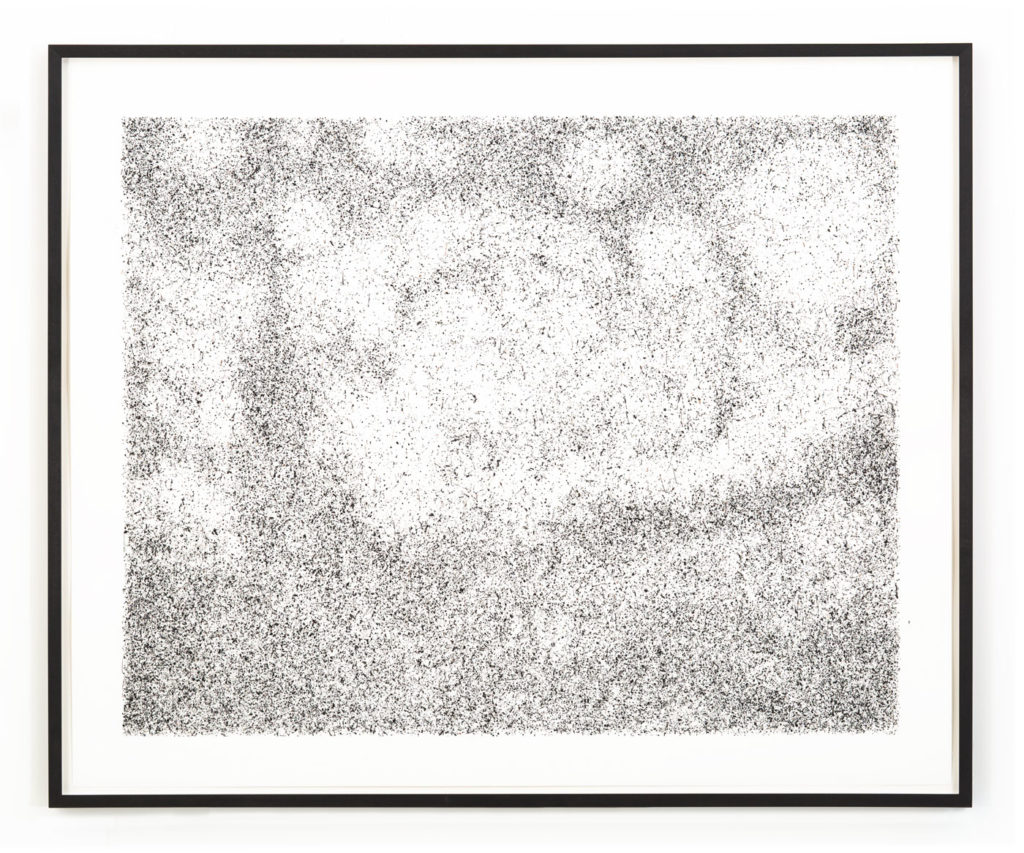

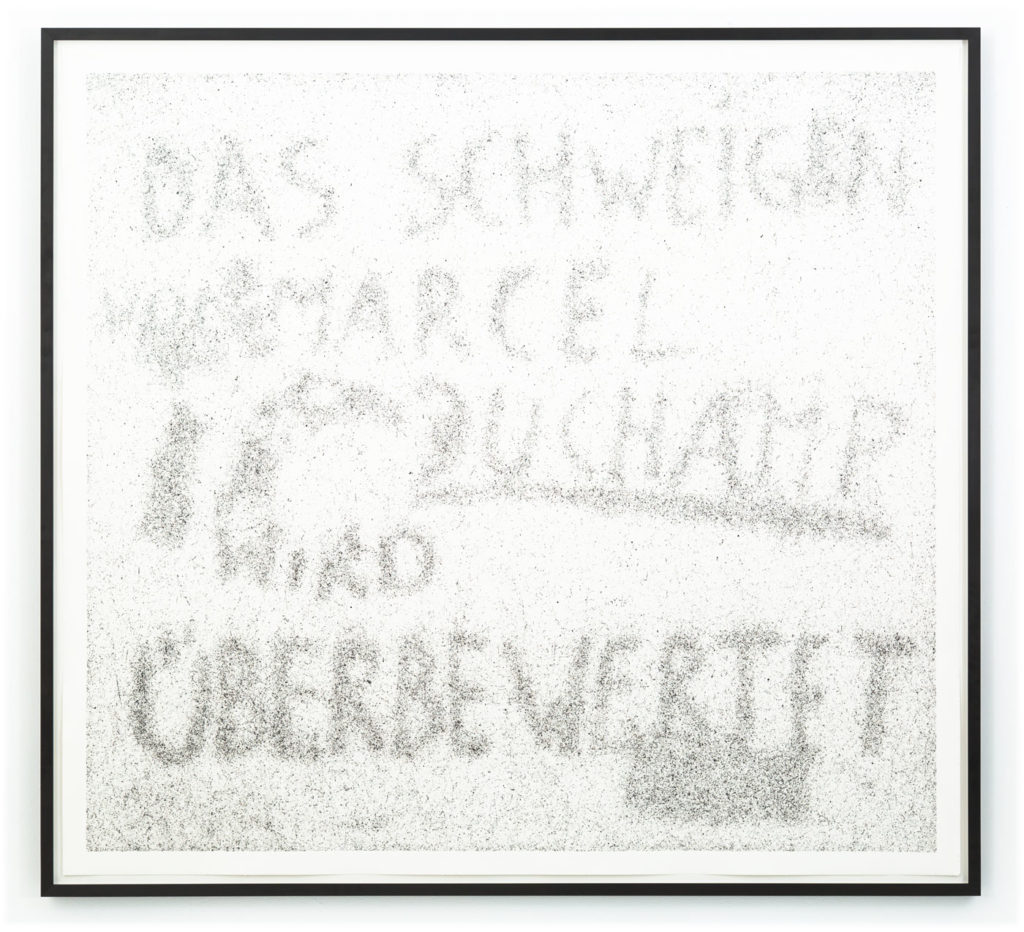

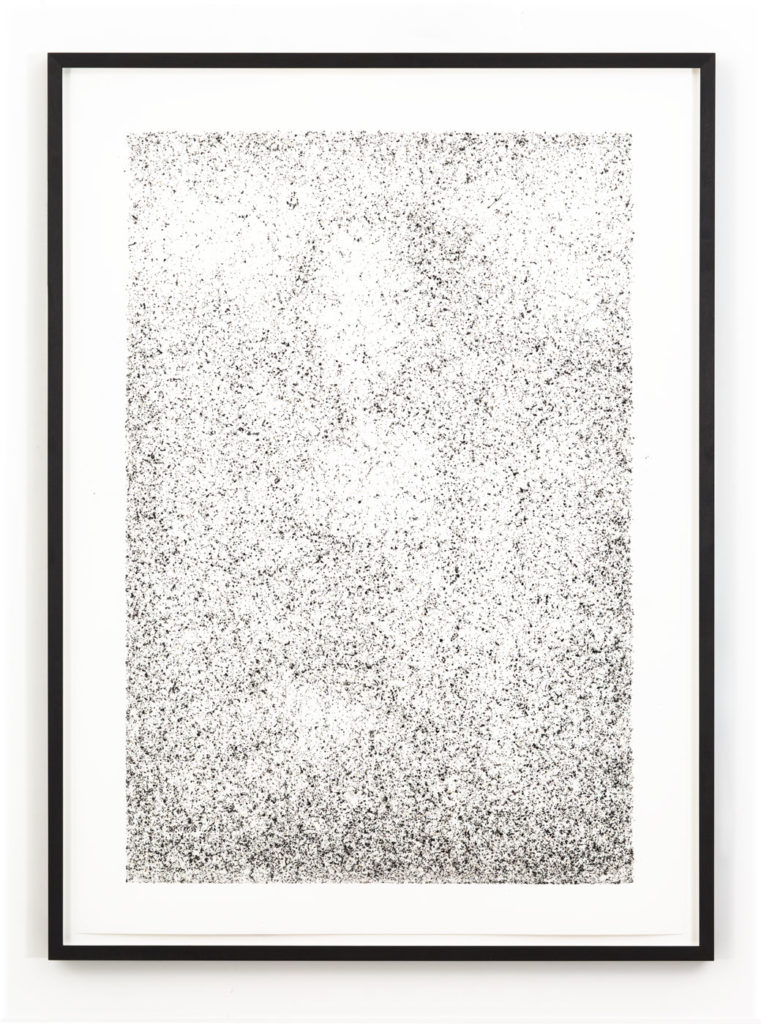

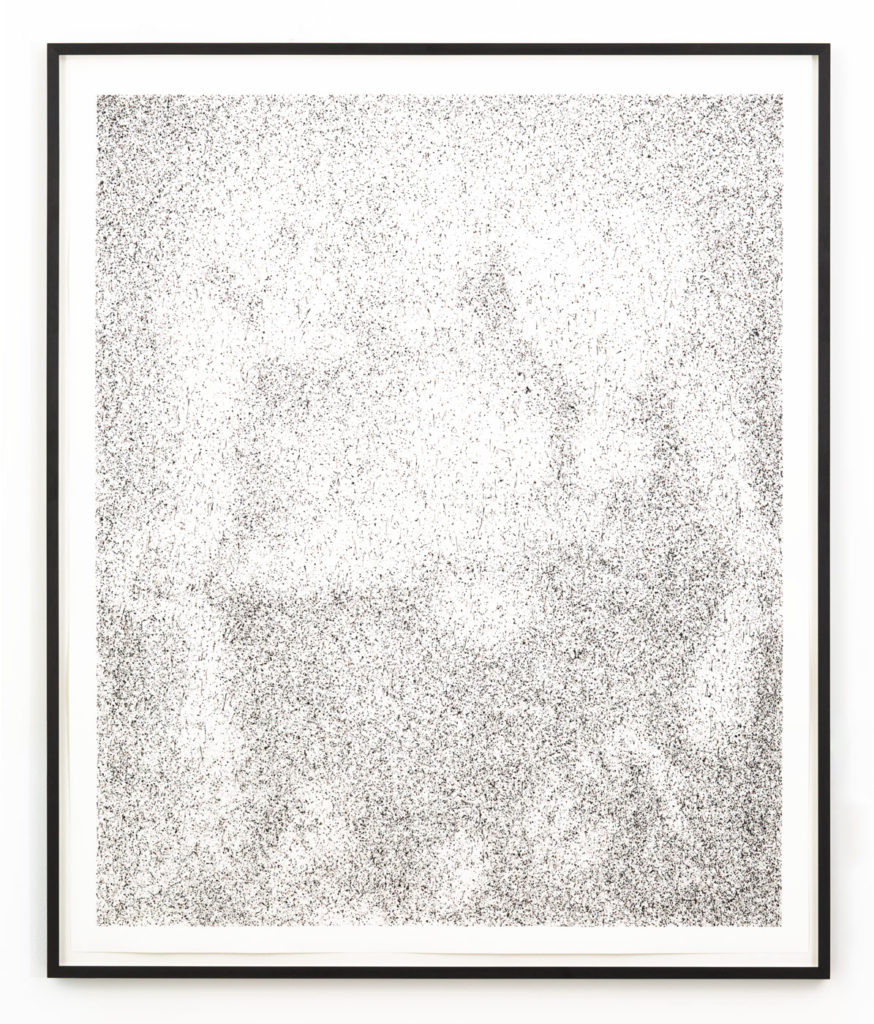

Detaching from the previous works, in the flies paintings the artists developed a new technique. As a meticulous scientist, he observed and studies the flies behavior. Thus, after discovering that they are attracted by heat, Prüfer came up with a technique which allows the flies to interpret and perform images. He obtained to make them move to preordained points, driving them to aggregate. The marks left by the flies are the result of the length of their stay and despite the blurriness, the resulting images are immediately recognizable: the Mona Lisa by Leonardo, The Origin of the World by Courbet, The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo… The subjects are famous iconographies existing in the world, and therefore in our mind.

A discourse on the collective creation of knowledge and its storage within the human mind is thus the main argument brought into play by Prüfer.

Fascination for footprints is taken as a starting point, for they represent a language: the primitives were able to read footprints and, by observing them, they could collect information. Drawing on this evolutionary heritage of our species, the author attempts to recall that type of semiotic exercise. He shows that by examining the insects’ footprints, we can understand the animals, but also the humans, both in our social and neurological mechanisms.

On the one hand, the experiments lead to investigate the degree of liberty, and thus creativity, when a given number of instructions is provided to the insects. On the other hand, Prüfer’s experimentations disclose a further reasoning, the one concerning the creation of culture as a collectiveness.

The new works are produced in crates that recall the honeybee boxes. The paintings are thus delivered, on the surface, as zoological experiments for the viewer’s scrutiny. The insects invite a kind of empathy, as with their often clumsy appearance they forfeit some of their fabled efficiency.

The artist observed some of the most significant behaviors of flies. If one fly moves to a point, the others tend to move there too. Secondly, when a source of heat is present, a large part of the swarm moves there.

In considering the above, we now start to see what Prüfer’s process is disclosing. When the individual acts in-group, two opposite situations may arise: complete chaos and loss of sense, or efficiency and creation of a bigger sense.

The latter generates results that would have been impossible if conducted individually.

In light of this, we understand that the flies could create the image we are observing only thanks to their collaborative work. Similarly, we humans need to rely on a collective knowledge to grasp and represent reality. The artist once again highlights the distinction between the individual and the group as a crucial subject in his work. His efforts address the self-strengthening process that originates when we produce culture in collectiveness. Far from any socio-political utterance, however, Prüfer’s main concern is to put in evidence the value of some intangible human connotations.

These works address an approach which is acutely semiotic and philosophical, bringing into play what has been identified by scientists as ”the collective brain”. It is demonstrated that information may be transmitted directly from one brain to another and that human intelligence is a joint phenomenon. The brain activity of a single human is not sufficient to create and preserve a durable knowledge. It is the common act of thinking, remembering and interpreting that ultimately generates a mutual human background.

Therefore, we are able to recognize those images produced by the insects, because they already exist in our brain as a shared code, which is present within every single mind, therefore within our collective brain. This one is indispensable not only for the creation of a collective knowledge but also for the storage and decodification of it.What the artist provides is a visible image of this phenomenon.

So, what are the “real things”, how do they constitute knowledge and how do they last through their representation?

Referring back to Plato, Prüfer depicts one of the possible answers to those ontological questions: the essence of things only lies in a collective knowledge.

Finally, we also encounter a double displacing of authority. Not only do these images exist thanks to the work of the flies, but also and more importantly thanks to the whole humanity, for their existence is possible only through a connected cognition. We are all authors, to some extent, of these images.

This new body of works explores a new path by involving, once again, the animals’ activity. Prüfer astutely nudges the enigmatic into the realm of the familiar, and through his tested collaboration with nature, his practice now emerges as an invitation to reflect on our shared knowledge as humans.

Text: Lucia Longhi